Lets find hardness in water: what causes that annoying scaling and lack of lather? Learn about temporary vs. permanent hardness, quick removal methods, measurement techniques, and the health limits you must know. Stop struggling with hard water today!

Have you ever wondered why sometimes your soap just refuses to foam, no matter how much you scrub, or why that annoying white layer seems to build up perpetually inside your pipes and teakettle.The culprit, my friends, is likely hardness in water. Understanding water quality is crucial, especially in fields like environmental engineering, where we constantly analyze water supply systems,.

We need to meticulously identify every parameter, understand the problems it causes, learn how to measure it accurately, determine its acceptable limits, and decide on the necessary treatment if the measured value exceeds those limits. Hardness is one of those crucial chemical water quality parameters we must master.

At its core, water hardness is simply a result of certain dissolved minerals floating around in your water. It’s an indicator that the water quality might be compromised or that it could cause issues in treatment plants or household fittings. The more of these specific minerals present, the harder your water is, and the more difficulties you will face.

Try Our Calculator:– Water Hardness Calculator

The Troublemakers: Understanding Multivalent Cations

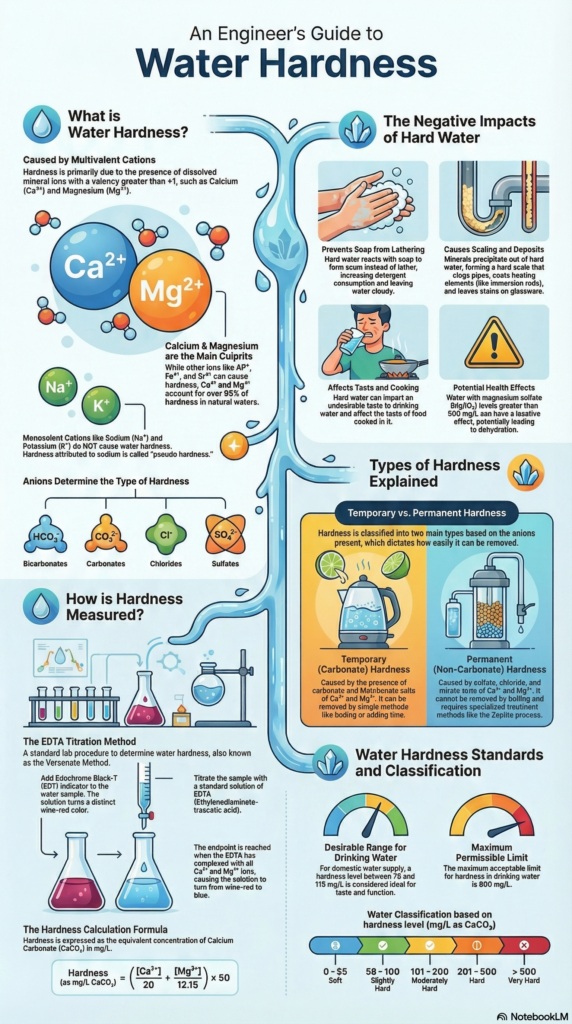

So, what exactly are these minerals? Hardness is fundamentally caused by the presence of multivalent cations. Now, don’t let that fancy name scare you! A multivalent cation is just an ion whose valence (or charge) is greater than one (like +2, +3, +4, and so on). Think of them as tiny, highly charged guests that crash the party and ruin the fun (like preventing lather from forming).

The usual suspects that cause the vast majority of water hardness are Calcium (Ca2+) and Magnesium (Mg2+). However, they are not alone. Other multi-valent cations like Iron (Fe3+), Aluminum (Al3+), and Copper (Cu2+) also contribute significantly to the total hardness of the water sample.

Generally speaking, the higher the concentration of any of these multivalent cations, the greater the resulting hardness will be. While we define hardness based on what causes the issue (the multivalent cations), we often quantify it by measuring the amount of dissolved Calcium and Magnesium specifically.

Why Single-Valent Ions Get a Free Pass

If Calcium and Magnesium are causing all this trouble, what about other common ions you might find in water, like Sodium (Na+) or Potassium (K+).These are known as single-valent ions (they only have a +1 charge). And here’s the key distinction: single-valent ions do not cause hardness.

Why? Because their chemical behavior and ability to react with soap or deposit scaling layers differ greatly from their multivalent counterparts. If you measure hardness and mistakenly include the concentration of Sodium, you actually end up calculating what is known as Pseudo Hardness, which means you are attributing hardness to an ion that cannot actually cause it.

The Tangible Impacts of Hard Water: Where We See the Damage

Hardness isn’t just an academic chemistry concept; it creates real, visible problems that affect our daily lives and our infrastructure,. It’s why we need to identify and treat it!

The Soap Scum Struggle: A Lathering Problem

One of the most immediate effects you notice with hard water is its frustrating inability to interact properly with soap or detergent. When you try to mix a soap solution with hard water, the expected outcome—a nice, bubbly lather—simply doesn’t happen. Instead, the soap reacts with the hardness-causing ions, and the water turns murky or cloudy.

This interaction means that your detergent is wasted trying to neutralize the hardness ions instead of cleaning your clothes or dishes. Consequently, you end up needing a much larger quantity of detergent to achieve any sort of cleaning action, which is definitely not cost-effective.

The Silent Destroyer: Scaling and Deposition

Perhaps the most destructive long-term effect of hard water is scaling. Imagine scaling as a creeping internal blockage, much like cholesterol building up in an artery. Hardness components, particularly when heated, start to deposit a hard layer onto surfaces.

You can see this effect everywhere hard water flows or is heated:

- Pipes and Fittings: These develop a hard layer that restricts flow and damages infrastructure.

- Utensils: Glasses and dishes often retain a visible film or layer.

- Heating Elements: Immersion rods used for heating water are prime targets. The hardness quickly deposits on the rod, reducing its efficiency and potentially damaging the element.

This deposition is often referred to as scaling, and it indicates that there is “something” in the water that actively deposits itself on fittings, utensils, or heating rods,.

Health Implications: More Than Just Taste

While hard water generally isn’t considered acutely dangerous, it certainly impacts the quality and taste of drinking water. In fact, we need a certain amount of hardness—around 75 to 115 mg/L—to ensure the water maintains an acceptable taste.

However, excessive hardness can lead to specific health issues, primarily linked to Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO4). If the concentration of MgSO4 exceeds 50 ppm (parts per million), it can create a laxative effect. In extreme concentrations, this can lead to severe dehydration.

The Chemistry of Hardness: Splitting the Difference (Temporary vs. Permanent)

Not all hardness is created equal! The specific type of anion that is paired with the multivalent cation determines whether the hardness is easy to remove or whether it’s highly stubborn. We generally classify hardness into two main types: temporary (or carbonate) and permanent (or non-carbonate).

The fundamental reality is that it’s the anions, dissociated from the multivalent cations, that ultimately cause the hardness,.

Carbonate Hardness: The “Temporary” Fix

Temporary Hardness is also known as Carbonate Hardness. This designation applies if the accompanying anions in the water are either Carbonate or Bicarbonate (HCO3−) .

For example, if Calcium (Ca2+) dissociates with Carbonate , or Magnesium (Mg2) dissociates with Bicarbonate, this results in temporary hardness,. These combinations are significant because they don’t just cause hardness—they also contribute to the water’s alkalinity,.

We call this “temporary” because, thankfully, it can be removed relatively easily, often just by simple boiling.

Non-Carbonate Hardness: The Stubborn “Permanent” Type

Non-Carbonate Hardness, or Permanent Hardness, is the tough one. This type occurs when the multivalent cations (like Ca2+ or Mg2+) are paired with anions other than carbonates or bicarbonates.

The main contributors to permanent hardness are Chlorides , Sulfates , and Nitrates . If these anions have broken off from a multivalent cation (like CaCl2 or MgSO4), they absolutely cause hardness,.

Why is it called “permanent”? Because non-carbonate hardness is much harder to eliminate. It will not be removed simply by boiling, meaning you need more sophisticated treatment methods.

Battling the Hardness: Removing the Unwanted Guests

If the water hardness measured value exceeds the permissible limits, or if it is causing significant scaling and soap wastage, then treatment is absolutely necessary. Since temporary and permanent hardness behave differently, they require different removal strategies.

Quick Fixes for Temporary Hardness: Boiling and Lime

Temporary hardness is often seen as the less problematic sibling because we have straightforward ways to eliminate it.

- Boiling: This is the easiest method. When you boil water containing temporary hardness (like dissolved Ca(HCO3)2), the heat causes the dissolved compound to precipitate out as a solid, such as CaCO3. Once precipitated, the solid can be easily separated from the water, and the hardness is considered removed.

- Adding Lime: Another chemical treatment involves adding lime (Ca(OH)2) to the water. This chemical reaction also causes the hardness components to precipitate out, allowing them to be removed.

Tackling Permanent Hardness: Ion Exchange Solutions

Permanent hardness does not respond to boiling. For example, if you boil Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO4), it remains in solution and the hardness persists. To effectively remove permanent hardness, we typically rely on the Zeolite or Ion Exchange method.

The Role of Sodium Exchange

In ion exchange, we leverage single-valent cations, specifically Sodium (Na+). Remember, sodium does not cause hardness. When hard water passes through an ion exchange medium (like zeolite), the pesky multivalent cations (Ca2+, Mg2+) are swapped out for harmless sodium ions. This effectively removes the hardness while keeping the overall mineral concentration relatively stable—a true chemical sleight of hand!

Quantifying Hardness: How We Measure Water Quality

If we don’t measure the hardness accurately, how can we possibly know if treatment is needed? Measuring hardness is a critical step in water quality control.

The Gold Standard: EDTA Titration Explained

The most common and robust modern technique for measuring total hardness is the EDTA Titration process,. EDTA (Ethylene Diamine Tetra Acetic Acid) acts as our standard solution or titrant.

Here is how the magic happens:

- Sample Preparation: You take your water sample (with unknown hardness). This water sample already contains the dissolved multivalent ions (Ca2+ and Mg2+).

- Color Induction: A specialized color indicator is added to the water sample. This indicator instantly grabs onto the Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions , forming a stable complex that displays a distinctive red wine color,.

- Titration and End Point: Now, you slowly add the EDTA solution, drop by drop. EDTA is even stronger than the indicator, so it begins to steal the Ca2+ and Mg2+ away from the indicator complex. As the EDTA effectively “captures” all the hardness ions, the color indicator is released back into the solution. The titration process is complete when the entire solution reverts to a colorless state—that colorless state is our precise measurement endpoint.

The Legacy Method: Using Soap Solution

Before the widespread use of methods like EDTA titration, one way to determine hardness was the Standard Soap Solution method (often associated with Clark’s Method). This method relies on the most basic impact of hardness: its reaction with soap.

In this process, you determine the hardness by finding the exact amount of a standard soap solution required to produce a permanent lather (stable foam) in a measured, known volume of water. More soap required means more hardness present.

Calculating Hardness: Expressing Results as CaCO3 Equivalent

Because hardness can be caused by various ions (Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe3+, etc.), we need a common baseline to compare them. We standardize all hardness measurements and express them in terms of milligrams per liter of Calcium Carbonate equivalent.

We calculate this equivalent value using a formula that relates the concentration of each multivalent ion to the equivalent weight of CaCO3.

For example, the calculation for Calcium and Magnesium hardness components involves:

Where 50 is the equivalent weight of CaCO3. This mathematical conversion allows us to compare different water samples accurately, regardless of which specific ion caused the hardness.

Understanding Your Water Grade: Permissible Limits and Degrees

Knowing how hard your water is only matters if you know what counts as “too hard”. We have specific regulatory guidelines and classification systems to grade water quality based on hardness values.

For domestic water supply, while soft water might seem ideal, a little hardness is beneficial: 75 to 115 mg/L (as CaCO3) is generally required to maintain a good taste. However, the maximum permissible limit for hardness is set at 600 mg/L. Anything above that certainly warrants mandatory treatment.

Defining Water Quality: Soft, Moderately Hard, and Very Hard

We use specific ranges of CaCO3 equivalent concentration to classify the water’s degree of hardness:

| Hardness Value (CaCO3 mg/L) | Degree of Hardness |

|---|---|

| 0 to 55 | Soft Water |

| 56 to 100 | Slightly Hard Water (or Moderately Hard) |

| 101 to 200 | Moderately Hard Water |

| 201 to 500 | Hard Water |

| > 500 | Very Hard Water |

If your water falls into the soft category (0 to 55 mg/L), you have little to worry about. If you are creeping up into the Hard or Very Hard ranges (over 200 mg/L), you will definitely be noticing the effects of scaling and poor lather,.

International Scales: Clark, American, and French Degrees

Just like different countries measure distance in inches, centimeters, or other units, historically, different regions developed their own criteria for defining a “degree” of hardness. These scales are primarily based on the concentration of salt in the water required to meet that definition.

- English (Clark) Degree: One Clark Degree of hardness is equivalent to 17.25 mg/L of the dissolved salt.

- American Degree: One American Degree of hardness is defined by 17.12 mg/L of the salt content.

- French Degree: This scale is simpler, with one French Degree representing 10 mg/L of the salt content in the water.

Pseudo Hardness: The Calculation Confusion

We briefly touched on this earlier, but it’s worth revisiting, as it can be a source of error in water testing. Pseudo Hardness occurs when you measure the total concentration of ions in the water and include single-valent ions, most commonly Sodium (Na+), in your calculation of hardness.

Since Sodium is a single-valent cation, it simply does not cause water hardness. However, if you mistakenly count the hardness contribution of sodium, you end up overestimating the true hardness of the water. Pseudo hardness is the value you calculate due to the presence of sodium ions, even though those ions are not responsible for the negative effects we associate with hard water,.

Conclusion: Making Peace with Hard Water

Water hardness is far more than just a minor annoyance; it’s a critical chemical parameter that dictates how water interacts with our homes, infrastructure, and even our bodies. Whether it’s the frustration of detergent failure or the slow, destructive buildup of scaling in your appliances, understanding the difference between temporary hardness (easy to remove by boiling) and permanent hardness (requiring methods like ion exchange) is vital for proper water management.

By utilizing advanced techniques like EDTA titration and adhering to maximum permissible limits—like the 600 mg/L threshold—we can ensure that the water delivered to consumers is safe, palatable, and won’t cause unnecessary damage. Water quality is a continuous conversation, and armed with this knowledge, you are now much better equipped to participate in it!

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Hardness in Water

Why doesn’t soap lather in hard water?

Hard water contains high concentrations of multivalent cations, such as Calcium and Magnesium. When soap is added, the soap reacts preferentially with these ions rather than mixing with the water to create foam or bubbles (lather). This reaction uses up the soap, causing the water to become cloudy and preventing the formation of lather.

Which ions cause hardness in water?

Hardness is primarily caused by the presence of multivalent cations—ions whose valency is greater than one. The main contributors are Calcium (Ca2+) and Magnesium (Mg2+), but other ions like Iron (Fe3+), Aluminum (Al3+), and Copper (Cu2+) also contribute,. Ions with a single positive charge, such as Sodium (Na+) and Potassium K+, do not cause hardness.

What is the difference between temporary and permanent hardness?

The difference lies in the associated anion. Temporary Hardness (or Carbonate Hardness) is caused by multivalent cations paired with Carbonateor Bicarbonate anions. Permanent Hardness (or Non-Carbonate Hardness) is caused when those same multivalent cations are paired with Chloride , Sulfate , or Nitrate anions. Temporary hardness can often be removed by boiling, but permanent hardness requires chemical treatment,.

What is the maximum acceptable limit for hardness in drinking water?

The maximum permissible limit for hardness in water, measured as CaCO3 equivalent, is 600 mg/L. For taste maintenance, a range of 75 to 115 mg/L is generally considered ideal.

Does hard water cause any health problems?

While typically safe, high levels of certain hardness components can have health impacts. Specifically, if Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO4) concentration is greater than 50 ppm, it can act as a laxative and may contribute to extreme dehydration conditions.